After six years of extensive archaeological excavations, researchers from the Israel Antiquities Authority and Tel Aviv University have uncovered a 220-meter-long section of an ancient street first discovered by British archaeologists in 1894.

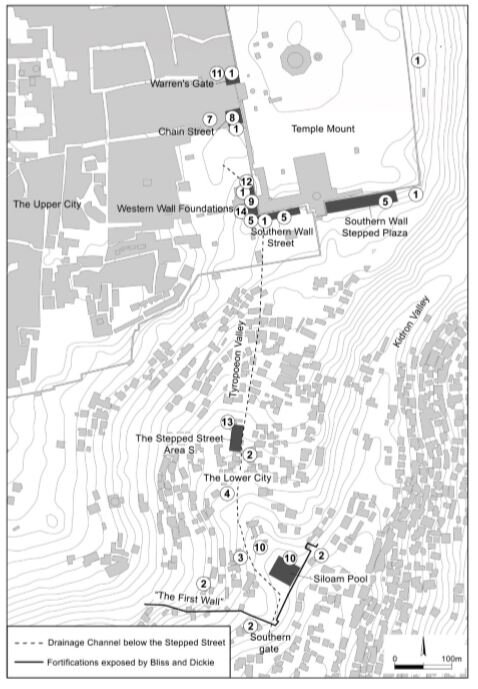

Archaeologists uncover 2,000-year-old street in Jerusalem built by Pontius Pilate: Location map marking excavation sites [Credit: Drawing: D. Levi, IAA; printed by permission of the Survey of Israel]

An ancient walkway most likely used by pilgrims as they made their way to worship at the Temple Mount has been uncovered in the "City of David" in the Jerusalem Walls National Park.

In a new study published in Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, researchers at the Israel Antiquities Authority detail finding over 100 coins beneath the paving stones that date the street to approximately 31 CE. The finding provides strong evidence that the street was commissioned by Pontius Pilate.

After six years of extensive archaeological excavations, researchers from the Israel Antiquities Authority and Tel Aviv University have uncovered a 220-meter-long section of an ancient street first discovered by British archaeologists in 1894. The walkway ascends from the Pool of Siloam in the south to the Temple Mount.

Both monuments are hugely significant to followers of Judaism and Christianity. The Temple Mount, located within the Old City of Jerusalem, has been venerated as a holy site for thousands of years. At the time of the street's construction, it is where Jesus is said to have cured a man's blindness by sending him to wash in the Siloam Pool.

The excavation revealed over 100 coins trapped beneath paving stones. The latest coins were dated between 17 CE to 31 CE, which provides firm evidence that work began and was completed during the time that Pontius Pilate governed Judea.

"Dating using coins is very exact," says Dr Donald T. Ariel, an archaeologist and coin expert with the Israel Antiquities Authority, and one of the co-authors of the article. "As some coins have the year in which they were minted on them, what that means is that if a coin with the date 30 CE on it is found beneath the street, the street had to be built in the same year or after that coin had been minted, so any time after 30 CE."

"However, our study goes further, because statistically, coins minted some 10 years later are the most common coins in Jerusalem, so not having them beneath the street means the street was built before their appearance, in other words only in the time of Pilate."

The magnificent street - 600 meters long and approximately 8 meters wide - was paved with large stone slabs, as was customary throughout the Roman Empire. The researchers estimate that some 10,000 tons of quarried limestone rock was used in its construction, which would have required considerable skill.

The opulent and grand nature of the street coupled with the fact that it links two of the most important spots in Jerusalem - the Siloam Pool and Temple Mount - is strong evidence that the street acted as a pilgrim's route.

"If this was a simple walkway connecting point A to point B, there would be no need to build such a grand street," says Dr Joe Uziel and Moran Hagbi, archaeologists at the Israel Antiquities Authority, co-authors of the study. "At its minimum it is 8 meters wide. This, coupled with its finely carved stone and ornate 'furnishings' like a stepped podium along the street, all indicate that this was a special street."

"Part of it may have been to appease the residents of Jerusalem, part of it may have been about the way Jerusalem would fit in the Roman world, and part of it may have been to aggrandize his name through major building projects," says author Nahshon Szanton.

The paving stones of the street were found hidden beneath layers of rubble, thought to be from when the Romans captured and destroyed the city in 70 CE. The rubble contained weapons such as arrowheads and sling stones, remains of burnt trees, and collapsed stones from the buildings along its edge.

It is possible that he had the street constructed to reduce tensions with the Jewish population. "We can't know for sure? although all these reasons do find support in the historical documents, and it is likely that it was some combination of the three."

Source: Taylor & Francis Group [October 20, 2019]

Pisidia Antiokheia'da tılsımlı kolye bulundu

Pisidia Antiokheia'da tılsımlı kolye bulundu  Türkiye Kültür Yolu Festivali'nin 2025 yılı takvimi belli oldu

Türkiye Kültür Yolu Festivali'nin 2025 yılı takvimi belli oldu  Giresun ve Samsun İl Kültür ve Turizm Müdürleri görevden alındı

Giresun ve Samsun İl Kültür ve Turizm Müdürleri görevden alındı  Kars'ta kaçak kazı yaparken yakalanan 6 defineciden 2'si Azerbaycan uyruklu çıktı

Kars'ta kaçak kazı yaparken yakalanan 6 defineciden 2'si Azerbaycan uyruklu çıktı