Arkeologlar, Tel Yehud'daki geniş bir Kenan nekropolünde bulunan 3300 yıllık seramiklerde afyonun kimyasal izlerini ortaya çıkardılar.

The discovery, published in July in the journal Archeometry, provides a window into the cult and burial practices of Levantine inhabitants during the Late Bronze Age. According to this article; The find also highlights the complexity and splendor of the extensive international trade networks of this period, as the drug is believed to have been imported from Cyprus on private label ships.

Archaeologists have unearthed chemical traces of opium in 3,300-year-old ceramics found in a vast Canaanite necropolis at Tel Yehud in present-day central Israel.

According to Ariel David from haaretz.com; Since the drug is believed to have been imported from Cyprus in specially-branded vessels, the find also highlights the complexity and grandeur of the vast international trade networks of this period.

Vanessa Linares: Morphine only comes from the opium poppy

A team led by Vanessa Linares, an archaeologist who specializes in identifying organic residues in ancient pottery, analyzed 22 vessels that were uncovered in a 2017 excavation of tombs in Tel Yehud, a site now part of the modern-day Israeli town of Yehud. Linares, who is now a fellow at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, conducted the analysis as part of her doctoral research at Tel Aviv University and the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot.

Using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry to analyze substances absorbed by the ancient clay, Linares and colleagues found that eight of the vessels from Tel Yehud once contained opium alkaloids – organic compounds derived from the poppy plant. These included morphinan, which is the decomposition product of morphine, opianic acid and other compounds that, taken together, form the unmistakable chemical signature of opium, Linares explains.

“Morphine only comes from the opium poppy, so you would not be able to contaminate the sample with something else, like a hand cream,” Linares says. It also helps that archaeologists working at Tel Yehud called her immediately after the discovery, enabling her to sample the ceramics still in the field.

The researchers weren’t looking for opium

“It’s a bit like forensics work, when there is a crime scene and the police call experts in to examine the site before it is contaminated, that’s what we do,” she explains.

The researchers weren’t necessarily looking for opium, and residue analysis is adept at identifying many different substances that ancient people may have used in their daily lives.

In the case of the 22 vessels included in the study, six contained fatty compounds indicative of the presence of some kind of vegetable oil, while the contents of eight more could not be identified. But the fact that that more than a third of the sample had once held opium points to the importance to the ancient Canaanites of the substance in the mortuary rituals – and perhaps other aspects of life, Linares says.

As to what exact purpose the drug served, we can only speculate, though the psychoactive, narcotic qualities of opium may have played a key role, she suggests.

Ron Be’eri: Tel Yehud part of a sprawling city of the dead

The tombs at Tel Yehud date to the 14th century B.C.E. – that is, the Late Bronze Age – and are part of a sprawling city of the dead that includes thousands of burials, says Ron Be’eri, an Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologist who took part in the dig directed by the IAA’s Eriola Jakoel.

We don’t know the ancient name of this necropolis or which specific settlements it served, Be’eri adds.

At the time, Canaan was controlled by Egypt and the two cultures strongly influenced each other, which is also visible in burial customs, Be’eri explains. So, like the ancient Egyptians, the Canaanites took pains to preserve the integrity of the body and left offerings of food, drink and other material goods so that the deceased could sustain themselves in the afterlife, he says

While this is purely hypothetical, the opium may have been intended for use both by the dearly departed to ease their passage into the next world, and also by the living, who may have actually consumed it at the funeral or during commemoration ceremonies to achieve an ecstatic state and commune with the dead (or think they were communing with the dead), Be’eri speculates.

The researchers are on firmer ground when it comes to the origin of the drug and the economic implications of its presence in the Levant.

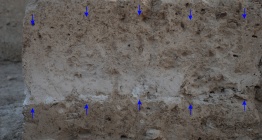

The highest concentration of opioid compounds was found in four so-called Base-Ring juglets, signature pottery vessels that experts know were made in Cyprus during the Late Bronze Age and exported across the Eastern Mediterranean.

Experts have suspected since the 1960s...

Smaller amounts of opioids were found in two locally-produced juglets and two storage vessels. This suggests that the product originally came in a concentrated liquid form from Cyprus, in the Cypriot juglets and was then poured into the local pottery in a more diluted form, either to stretch out the drug or to “cut” it, rendering it less potent, Linares says. That is exactly how modern dealers of opiates handle long-distance trade: they export concentrated versions and it gets “cut” by subsequent dealers.

In fact, since the 1960s, experts have suspected that Base-Ring juglets were specifically made to contain opium exported from the island. Their distinctive long neck makes these jugs look somewhat like an inverted poppy seed head, while the white bands that decorate them are reminiscent of the milky latex of the plant from which opium is extracted.

Ancient Tupperware

Aided by the recent improvement in residue analysis techniques, the debate on the purpose of Base-Ring juglets has gone back and forth in the last years. A 2015 study of four of these vessels found in Israel showed no sign of narcotics, and the authors concluded instead that these exquisite Cypriot ceramics were used to store aromatic oils.

Conversely a 2018 analysis of a single Base-Ring juglet from the British Museum did find traces of opioids, but that vessel was unprovenanced, undated and had been sitting on a museum shelf for years, leaving open the possibility of contamination, Linares notes.

The findings from Tel Yehud strongly support the idea that the Base-Ring juglet was indeed an early example of branding, a vessel made specifically to market its content, the researcher says.

The fact that analyses of these juglets don’t always uncover opioid compounds is probably due to the fact that, like most things in antiquity, the vessels would have been reused for other purposes once the original product ran out.

“These vessels are very unique and special and the locals put their best product inside them,” she says. “I believe they came over with opium and if they were reused, just like you reuse your Tupperware, they reused them for other unique and exotic products.”

While these Cypriot ceramics from the Late Bronze Age represent the earliest direct evidence of opium use, we know that humans had been getting high on this drug (and other substances) for far longer.

Neolithic communities in Western Europe may have cultivated the poppy plant more than 6,000 years ago. The Sumerians reveal in clay tablets from Nippur that they used opium for religious purposes and named it “Gil,” the same word for “happiness” (incidentally, also still a popular Hebrew name).

The ancient Egyptians and the Greeks also used opium for cultic practices and its soporific, painkilling properties. Later on, in the Iron Age, we also know that the ancient Israelites used psychoactive drugs like cannabis in their rituals, as evidenced by residue of this substance found on an altar at a ninth century B.C.E. shrine in Arad, southern Israel.

During the Late Bronze Age, the main cultivation hub for the poppy plant was Anatolia, from where the product made its way to Cyprus, whence it was then redistributed around the Mediterranean basin, Linares says.

Researchers have long understood that the Bronze Age was a time of early globalization, or “bronzization” as some call it, which saw great civilizations rise and trade everything from exotic fruits to precious metalsacross thousands of kilometers. Now it seems we can add opium to the list.

The new study from Tel Yehud “shows how vast the trade network was, how interconnected the ancient Near East was and the scale of the operation that was able to transport these goods from the Black Sea region down to the Levant through Cyprus,” Linares says.

“A lot of people think ancient people were very primitive and not as clever as we are today but I believe that technology was more advanced than we know and their operations far larger than we think,” she concludes. “So it’s important to keep in mind we are not so different from them today.”

Source: www.haaretz.com

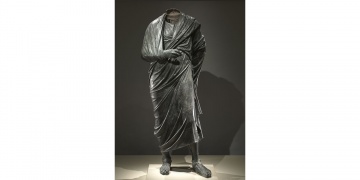

İsfahan Ali Minaresi Selçuklu Dönemi'nin ihtişamını yınsıtıyor

İsfahan Ali Minaresi Selçuklu Dönemi'nin ihtişamını yınsıtıyor  Pamukkale ve Hierapolis Antik Kenti'ni 25 yılda 37 milyon kişi ziyaret etti

Pamukkale ve Hierapolis Antik Kenti'ni 25 yılda 37 milyon kişi ziyaret etti  Bolu Valiliği, tabiat ve milli parkların korunmasına yönelik önlemleri açıkladı

Bolu Valiliği, tabiat ve milli parkların korunmasına yönelik önlemleri açıkladı  Türkiye 23 yılda 13 bin 282 tarihi eserini geri aldı

Türkiye 23 yılda 13 bin 282 tarihi eserini geri aldı