The great majority of the Sangiorgi gems were acquired before World War II, and many derive from notable earlier collections amassed by Lelio Pasqualini, the Boncompagni-Ludovisi family, the Duke of Marlborough, and Paul Arndt in Munich.

The J. Paul Getty Museum acquired at auction last week a group of seventeen ancient engraved gems from the collection of Roman art dealer Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886-1965). The great majority of the Sangiorgi gems were acquired before World War II, and many derive from notable earlier collections amassed by Lelio Pasqualini, the Boncompagni-Ludovisi family, the Duke of Marlborough, and Paul Arndt in Munich. Comprising some of the finest classical gems still in private hands, the Sangiorgi gems were brought to Switzerland in the 1950s and have remained there with his heirs until now.

Roman black chalcedony intaglio portrait of Antinous, circa 130-138 AD [Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

The group acquired by the Getty includes Greek gems of the Minoan, Archaic and Classical periods, as well as Etruscan and Roman gems, some of which are in their original gold rings. They have never been on public view and were only recently published for the first time in Masterpieces in Miniature. Engraved Gems from Prehistory to the Present (London and New York, 2018) by Claudia Wagner and Sir John Boardman.

“The acquisition of these gems brings into the Getty’s collection some of the greatest and most famous of all classical gems, most notably the portraits of Antinous and Demosthenes,” explains Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Minoan blue chalcedony tabloid seal with three swans, Late Palace Period, circa 16th cent. BC

[Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

Greek carnelian scarab with a nude archer, Archaic Period, circa early 5th cent. BC

[Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

Greek banded agate scaraboid with a warrior, Late Archaic Period, circa 475 BC

[Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

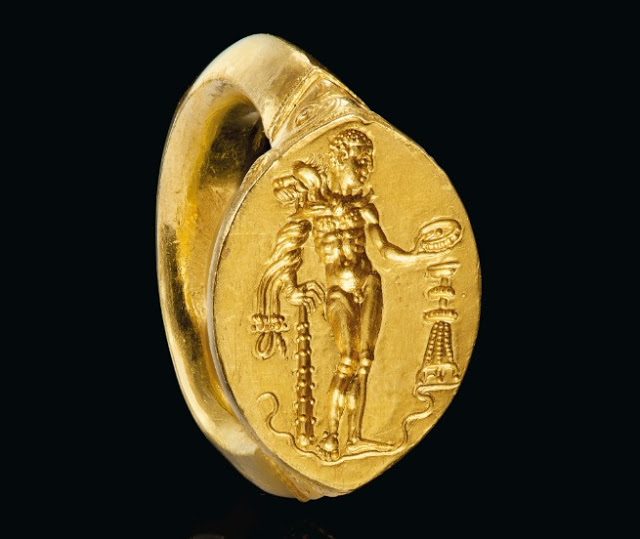

Greek gold finger ring with Herakles, Classical Period, circa Late 5th/Early 4th cent. BC

[Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

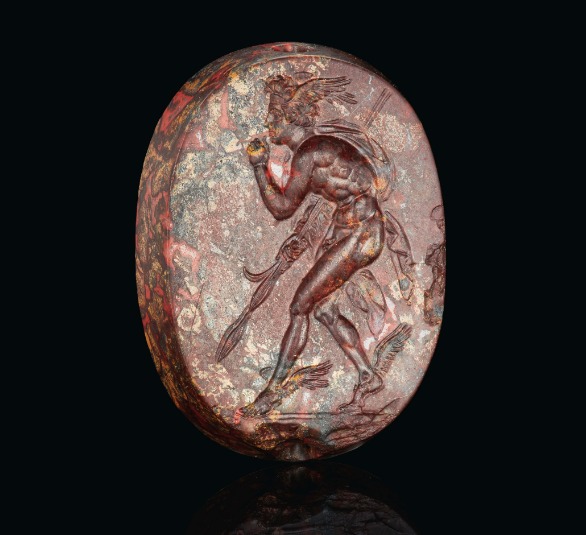

“But the group also includes many lesser-known works of exceptional skill and beauty that together raise the status of our collection to a new level. Two such are the image of three swans on a Bronze Age seal from Crete, which has an elegance and charm transcending its early date (c. 1600 B.C.); and the image of the semi-divine Perseus, a marvel of minute naturalism that cannot fail to enthrall. This acquisition represents the most important enhancement to the Getty Villa’s collection in over a decade.”

Highlights from the acquisition include two of the greatest known ancient gems: a Roman intaglio portrait of Antinous, superbly engraved in black chalcedony circa 130-138 A.D., and a Roman amethyst ringstone with a portrait of Demosthenes, signed by the artist Dioskourides, circa late 1st century B.C.

Greek mottled red jasper scaraboid with Perseus, Classical Period, circa 4th cent. BC

[Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

Greek gold and carnelian scarab swivel ring with crouching Aphrodite, Classical Period, circa 4th cent. BC

[Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

Greek carnelian scaraboid with Protesilaos, Classical Period, circa 4th cent. BC

[Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

Graeco-Persian banded agate scaraboid with a Greek-Persian combat scene, circa mid 5th cent. BC [Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

The gem portraying Antinous, the young lover of the Emperor Hadrian (ruled 117-138 A.D.), was engraved on an unusually large black chalcedony stone. Depicted in the guise of a hunter, Antinous wears a cloak over his shoulders pinned in place by a circular fibula and carries a spear. His idealized facial profile features a rounded chin, full lips and thick hair arranged in luscious curls that cover his ears and fall along his neck. The extraordinary quality of the engraving has led many to proclaim this the finest surviving portrait of Antinous in existence in any medium and one of the finest classical gems to have survived since antiquity.

Known as the Marlborough Antinous, it passed through many distinguished collections since its rediscovery, probably in the early eighteenth century. So great was the mania inspired by this gem that its first documented modern owner, the Venetian collector Anton Maria Zanetti (1679-1767), supposedly said that he would have sold his house to buy it. From him the gem was purchased by George Spencer (1739-1817), the 4th Duke of Marlborough, who wrote that it was “of an incredible beauty,” making it the highlight of perhaps the most extraordinary collection of antique gems ever assembled. It was sold at auction with the entire Marlborough Collection of gems to David Bromilow in 1875 and then separately in 1899 to Charles Newton Robinson, whose collection was in turn dispersed at auction ten years later. It was acquired at auction in 1952 in London by Sangiorgi who considered it an “excellent work of courtly art comparable with the most celebrated portraits of Antinous….”

Etruscan gold and carnelian scarab finger ring with Aplu/Apollo, circa 4th cent. BC

[Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

Etruscan carnelian scarab with the Rape of Cassandra, circa mid 5th cent. BC

[Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

Roman carnelian ringstone with a portrait of Octavian, circa mid-1st cent. BC

[Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

Roman amethyst ringstone with a portrait of Demosthenes, signed by Dioskourides,

circa late 1st cent. BC [Credit: © 2019 Christie’s Image Ltd]

The extraordinary frontal portrait of Demosthenes, the 4th century B.C. Greek orator, is the other great masterpiece of the Sangiorgi collection. It is signed by the gem engraver Dioskourides, who is mentioned by ancient writers as the court gem engraver to the emperor Augustus (ruled 27 BC-AD 14) and is today regarded as one of the greatest gem engravers of Roman times. The intaglio image is cut so deeply that the impression stands out in unusually high relief, reading more like a statue in the round. Demosthenes wears a mantle over one shoulder and turns his head slightly to one side. The orator is bearded, with a full mustache framing his lips. His brows are knitted and his forehead creased, giving him a seriousness of expression appropriate to the subject of his famous Philippics.

When it was in the collection of the Roman collector Lelio Pasqualini (1549-1611), the gem piqued the interest of every antiquarian, Grand Tour traveler, and glyptic scholar of the day, and its renown has only increased over time.

All seventeen gems will be featured as part of a special exhibition opening at the Getty Center in December highlighting recent acquisitions. Following that, they will go on view at the Getty Villa.

Source: The J. Paul Getty Museum [May 09, 2019]

Bulgaristan geleneksel festivalleriyle ve bayramlarıyla dikkati çekiyor

Bulgaristan geleneksel festivalleriyle ve bayramlarıyla dikkati çekiyor  Türkiye'deki tescilli mağaralarda 30 memeli türü ve endemik canlılar keşfedildi

Türkiye'deki tescilli mağaralarda 30 memeli türü ve endemik canlılar keşfedildi  Teos Antik Kenti'ndeki Dionysos Tapınağı'nda kazı ve restorasyon çalışmaları devam ediyor

Teos Antik Kenti'ndeki Dionysos Tapınağı'nda kazı ve restorasyon çalışmaları devam ediyor  Gümüşhane Karaca Mağarası'nda turizm sezonu başladı

Gümüşhane Karaca Mağarası'nda turizm sezonu başladı